General Motors Redefines Waste

“What some people call waste, we call a resource out of place.”– John Bradburn, Global Manager of Waste Reduction, General Motors

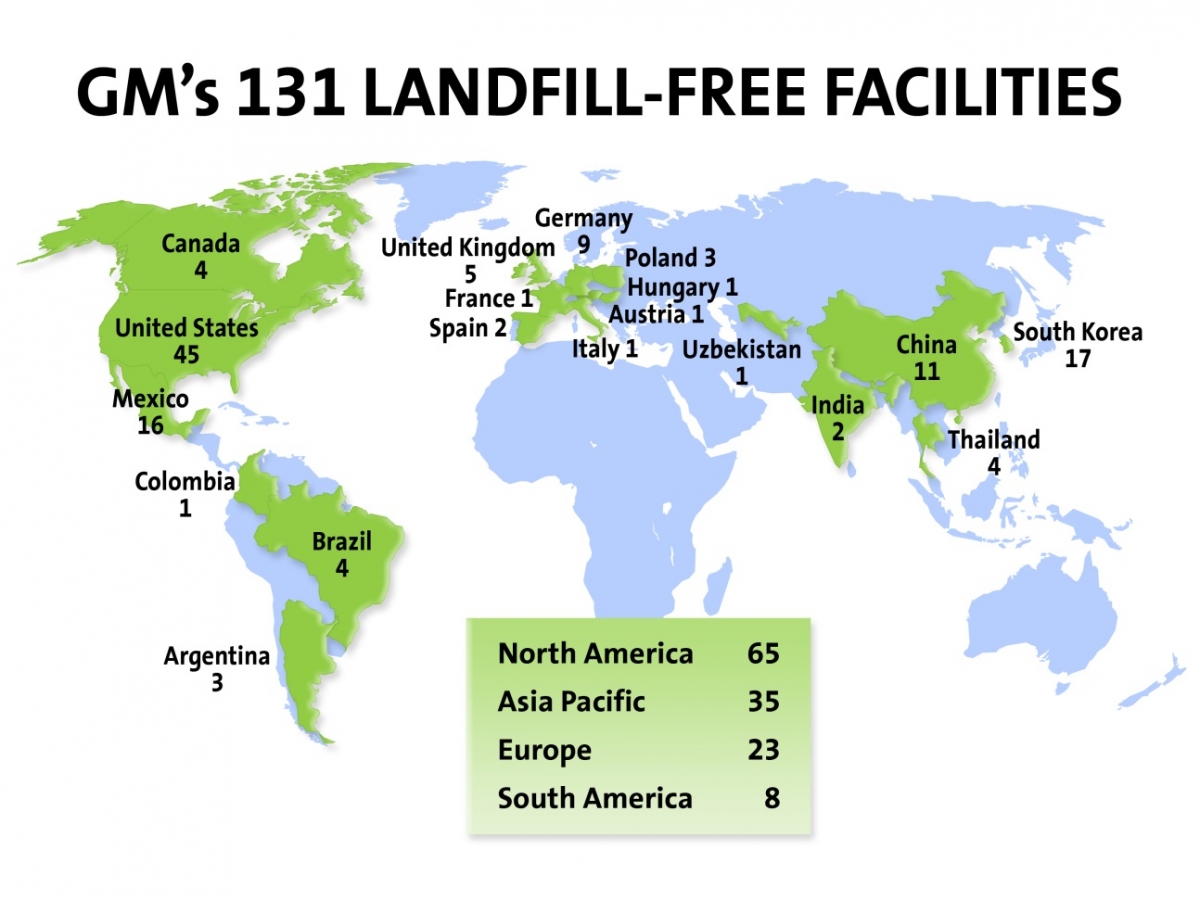

General Motors (GM) produces nearly 10 million vehicles annually with the help of 212,000 employees on six continents and does so while reusing or recycling 85% of its manufacturing waste generated worldwide. The automotive giant’s impressive diversion rate is due in large part to its 131 landfill-free facilities, 90 of which are manufacturing facilities. GM certified its first landfill-free facility on March 17, 2005, recognizing that good waste management was also good business. Recycling revenues now reach $1 billion annually. While goals related to reduction, reuse and recycling were in place well before 2005, GM formalized its landfill free goal in 2011 of 100 landfill-free manufacturing sites and 25 landfill-free non-manufacturing sites by 2020. After having achieved significant success, GM affirmed and increased their commitment in 2015 by joining the Obama Administration and Secretary John Kerry in the American Business Act on Climate Pledge. In addition to other climate related commitments, GM pledged to reduce total waste by 40% from its 2010 baseline and to achieve 150 landfill-free facilities by 2020.

A global standard for landfill-free, zero landfill, and zero waste designations does not yet exist, but it is generally considered to be a waste diversion rate above 90% to 95%. For GM, Bradburn explains, “it means 100% of all daily operational materials are to be managed in a way other than landfill to drive improvement in ways such as material substitutions and reuses.” Recognizing that “perfection in our world does not exist,” Bradburn clarified that GM does allow for the risk of residue up to 1% of a facility’s annual total waste. (Residue is the material sent to a processor with the intent of reuse or recycling that for some reason cannot be processed and still ends up in landfill.) On average, GMs landfill-free facilities reuse or recycle 97% of their waste, converting only 3% to energy using the following prescribed hierarchy of waste disposition:

Eliminate or reduce the amount of byproduct materials

Reuse materials onsite

Reuse materials offsite

Recycle materials onsite

Recycle materials offsite

Compost on or offsite

Recover energy from materials through incineration on or offsite

This standardized method for managing waste allows GM to internally verify its landfill-free facilities. “We believe that maintaining a common and consistent definition with steps and procedures goes a long way,” confirmed Bradburn. A crucial initial step is simply waste tracking. Every month GM’s facilities around the world return data on their over 15,500 byproduct streams and how they were handled. GM’s data collection system is what Bradburn calls the “physical backbone” of the program, adding, “Any good system or program really needs data to understand performance.” All GM facilities track their waste, but the landfill-free facilities must also have their outside processors periodically verify that their residue is less than 1% of the facility’s annual waste. However, as GM’s intention is not to send materials out in the first place, if a particular stream is shown to be a continual problem, Bradburn explained, “then we really bear down and try to substitute it with a new material on the design side or to find or create a new outlet [for the stream.]”

GM tackles its difficult waste streams primarily through knowledge sharing and creative thinking. Not only does GM have waste streams that Bradburn termed “tricky,” ranging from scrap metal and battery covers to grinding swarf and process pit sludge, but it also operates in 30 countries with variable recycling infrastructures. Bradburn, therefore, organizes monthly calls with subject-matter experts from GMs plants around the world to exchange knowledge and share best and innovative practices. In many cases, GM has gone beyond traditional recycling by repurposing byproduct streams into new vehicle components and products that benefit the communities in which it operates. The key, Bradburn shared, “is not just seeing something as it was intended to be, but what it can become.” For example, GM reuses cardboard shipping materials as sound dampening material in its Buick Lacrosse and Verano; it shreds test tires from the Milford, Michigan Proving Ground facility for use in air and water baffles in a variety of vehicles; and it even repurposes paint sludge as plastic shipping containers for some of its engine components. (Source: GM Waste Reduction Fact Sheet.)

Through these recycling and reuse programs, GM prevents 2.2 million tons of waste from going to landfill. As most of this waste is revenue generating, GM can afford to look at many impact factors when evaluating potential reuse projects. “When we do some of these projects, we want the business case,” explained Bradburn, “but that doesn’t mean that if it shows a slight negative that we don’t do it anyways.” For example, GM has converted about 1,600 steel baskets that formerly held parts from Korea into raised beds for urban gardens around Detroit. Though GM could recover value from the steel baskets, Bradburn justified the decision not to do so, “we think that the revenue loss, which is not a lot, is much outweighed by the fact that it is benefiting people.” In addition to the urban garden initiative, GM also donates vehicle sound absorption material to the Empowerment Plan to insulate coats that also serve as sleeping bags for the homeless and has repurposed over 800 Chevrolet Volt battery covers as nesting boxes to promote wildlife preservation.

Through these recycling and reuse programs, GM prevents 2.2 million tons of waste from going to landfill. As most of this waste is revenue generating, GM can afford to look at many impact factors when evaluating potential reuse projects. “When we do some of these projects, we want the business case,” explained Bradburn, “but that doesn’t mean that if it shows a slight negative that we don’t do it anyways.” For example, GM has converted about 1,600 steel baskets that formerly held parts from Korea into raised beds for urban gardens around Detroit. Though GM could recover value from the steel baskets, Bradburn justified the decision not to do so, “we think that the revenue loss, which is not a lot, is much outweighed by the fact that it is benefiting people.” In addition to the urban garden initiative, GM also donates vehicle sound absorption material to the Empowerment Plan to insulate coats that also serve as sleeping bags for the homeless and has repurposed over 800 Chevrolet Volt battery covers as nesting boxes to promote wildlife preservation.

Pictured above: Cadillac Urban Gardens on Merritt in Southwest Detroit. (Photo by John F. Martin for General Motors.)

Ultimately, none of these programs would be possible without employee buy-in and participation. “Everybody touches waste,” Bradburn pointed out, “and everyone can impact it positively or negatively in the decisions they make, in the things that they do, and in their attitude.” To ensure that its workforce positively impacts waste disposition, GM engages its 212,000 employees through specific demonstrations that build excitement and keep personnel informed. Bradburn stressed the importance of communication in accomplishing GM’s landfill-free goals, adding, “When our employees know that when they put something in a recycling bin that it becomes part of a vehicle and the specific vehicle part, it makes them feel good because it means they are part of the system and understand what happens.” With this understanding and corporate support of waste reduction goals, GM employees have even taken on their own projects like preparing the “Sustainable Living” meeting space pictured above or working to create a prototype chair and desk for school-aged children from large pallets shipped from Austria.

GM has made significant progress towards achieving its landfill-free goals: rethinking and repurposing its "resources" and minimizing its landfill usage. When asked where he saw future opportunities, Bradburn described an increasingly collaborative scenario where disparate industries communicate regularly to find beneficial byproduct synergies, adding, “We have to make sure we share ideas in resource conservation and create circular economies.” Having a waste whiz like Bradburn is certainly helpful when looking at material byproducts, but even he humbly pointed out that the opportunities in waste diversion will require more cross-sector collaboration, "It is going beyond just an individual like me knowing a little about this subject."

Pictured right: Team of GM employees in Zaragoza, Spain Plant Furnished a “Sustainable Living” Meeting Space using waste from the Assembly Plant. (Source: “Furnishing Gm’s Space with Reclaimed Waste.”)

© The George Washington University. All Rights Reserved. Use of copyrighted materials is subject to the terms of the Licensing Agreement.