General Services Administration

“GSA stands ready to assist our partner agencies with this [E.O. 13693] requirement as we collectively develop best practices for integrating climate performance measures into our procurements.” – Kevin Kampschroer, Chief Sustainability Officer, General Services Administration

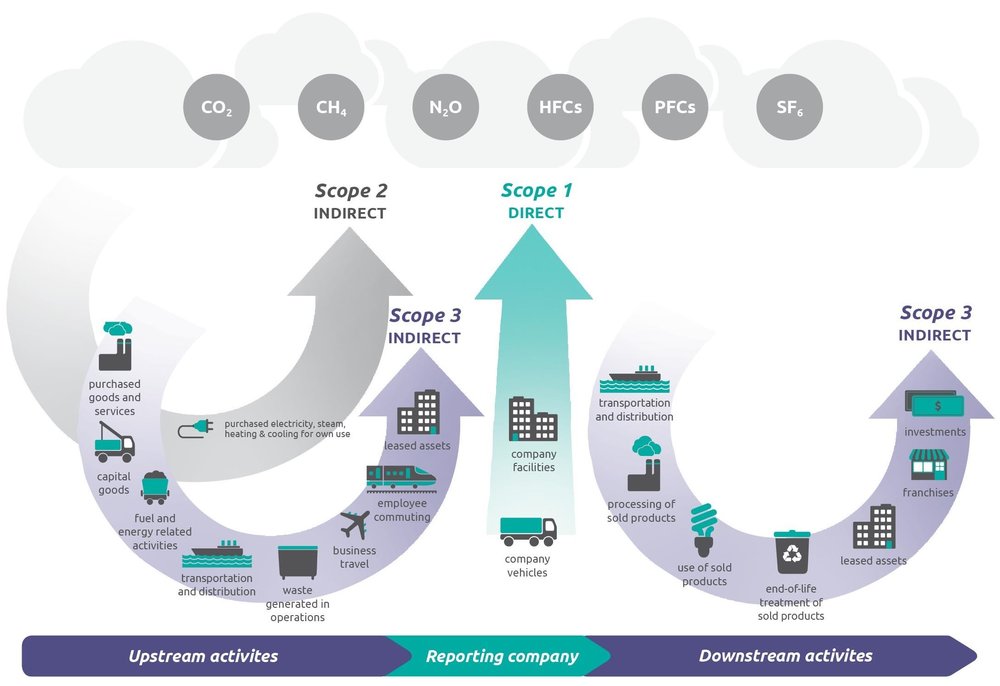

Climate change has become an ever-pressing global issue with companies, organizations, and governments increasingly making public commitments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Unfortunately, many of those same companies and governments are finding that the majority of their emissions are outside of their direct operations or control. The GHG Protocol has grouped GHG emissions into three scopes: Scope 1 emissions are direct emissions from an entity’s owned or operated assets such as facilities or vehicles; Scope 2 emissions are the indirect emissions from purchased electricity; and Scope 3 emissions are all of the upstream and downstream emissions across the value chain (see figure below). While Scope 3 emissions include employee business travel and employee commuting, this case study will focus on the management of the other emission categories listed.

Overview of GHG protocol scopes and emissions across the value chain. Source: GHG protocol, corporate value chain (scope 3) accounting and reporting standard.

Why look at your supply chain?

The Federal Government, with an annual spend of $445 billion on goods and services, has the immense opportunity to leverage its spend to reduce GHG emissions throughout its vast supplier network. Executive Order (E.O.) 13693 expanded upon and updated Federal environmental performance goals “with a clear overarching objective of reducing greenhouse gas emissions across Federal operations and the Federal supply chain.” Specifically, E.O. 13693 requires the seven largest procuring agencies to include “contract requirements for vendors or evaluation criteria that consider contractor emissions and greenhouse gas management practices” in at least five new contracts annually beginning in fiscal year 2017. Considering this requirement, the White House Council on Environmental Quality and the George Washington University Sustainability Collaborative convened a GreenGov Dialogue on Supply Chain Management of public, private, and NGO representatives to explore the motivations for supply chain GHG emission management and the associated challenges.

Betty Cremmins, Senior Manager at CDP Supply Chain, attended the Dialogue, bringing with her the most recent findings from the 2016 report, “From Agreement to Action: Mobilizing suppliers toward a climate resilient world.” Based on the responses of over 4,000 companies reporting to the CDP at the request of its seventy-five supply chain program members, CDP found that “supply chains are critical levers for action, with GHG emissions at least twice as large as a company’s operational Scope 1 and 2 emissions.” The potential impact of reducing supply chain emissions is therefore critical not only from a climate change perspective, but also from cost reduction and risk mitigation perspectives. Cost reduction is a primary driver of supply chain GHG reduction initiatives as it contributes to a company’s bottom line, is generally already aligned with traditional procurement practices, and can be easily measured with financial tools already in place. Similarly, risk mitigation drives supply chain management actions from a largely financial perspective as companies are increasingly aware of the potential operational disruptions associated with climate change related events such as extreme weather, hurricanes, coastal flooding, and water shortages. In fact, 72% of the suppliers who responded to CDP’s 2015 questionnaire identified regulatory, physical, and/or other climate risks “that may significantly affect their business operations, revenue, or expenditures.” Risk mitigation can be viewed as a cost reduction strategy aimed at avoiding financial risk from issues like damaging brand image, volatile raw material prices, supply chain disruptions, and compliance issues. Frankly, as Cremmins put it, “If you are not looking beyond your own four walls, you are really missing the greatest risk and therefore the greatest opportunity to really drive action in this [supply chain] space.”

From Measurement to Management

Once a company appreciates the potential opportunities associated with supply chain management and GHG emission reductions, there is still the matter of inspiring action from the supplier. GreenGov Dialogue participants identified several challenges associated with supply chain engagement. One of these challenges was the hesitancy of organizations to set concrete Scope 3 reduction goals because of a lack of direct control. While buyers can leverage their business or other enticements, they cannot actually control supplier practices. Suppliers also suffer from what is termed “survey fatigue,” the result of countless requests for information. Evan Van Hook, Corporate Vice President for Health, Safety, Environment, Product Stewardship & Sustainability for Honeywell International, stressed the significance of accurate data and information sharing, deeming it “critically important.” Unfortunately, when suppliers experience survey fatigue they may not report any information at all or they may report inaccurate data. Rachael Jonassen, Professorial Lecturer and Visiting Scholar at George Washington University, also pointed out how buyers fail to harmonize the metrics they use, further exacerbating the data collection struggle. Companies and organizations often think that they are unique in their operations and set out to create new strategies when in reality they share suppliers with other industry leaders. Communication not only between buyer and supplier, but also between industry peers Cremmins noted the importance of “being humble, starting from the point where everyone else is and taking the existing data and the existing programs.” This strategy then helps everybody move forward, reducing survey fatigue and over-reporting and allowing suppliers to focus on the actual emission reduction strategies. The 2016 CDP report also found that combining supplier requests greatly increased supplier response rates. When one member requested supplier disclosure, the average response rate was 41%, but when two members sent requests the response rate increased to 74%. Once five CDP members requested disclosure from a single supplier, the response rate jumped even higher to 93%.

Targeted supplier engagement and education was another strategy that emerged to combat survey fatigue. Climate risk and emissions vary greatly by industry and geography. Van Hook underlined materiality of data, “some areas in a supply chain will be much more important than others and the amount of effort devoted should be commensurate.” It would not make sense to spend resources to get a relatively low risk, low emitter to measure and reduce emissions that would not impact one’s carbon footprint. There are different ways to decide which suppliers to target, but companies usually first look at procurement spend, heavy emitters, and high risk suppliers.

The Good News

GSA Leading the Way

Though the General Services Administration (GSA) is not a corporation, it is tasked with the mission to “deliver the best value in real estate, acquisition, and technology services to government and the American people.” Sometimes called “the government’s office manager,” GSA has over $50 billion in managed spend annually. E.O. 13693’s predecessor, E.O. 13514, “Federal Leadership in Environmental, Energy, and Economic Performance, “ issued October 5, 2009, asked agencies to research ways in which reduce GHG emissions along federal supply chains and to determine evaluation factors. GSA swiftly began looking for best practices to leverage the purchasing power of the Federal Government to reduce emissions outside of actual federal footprint.

The GSA’s two largest offices are the Public Building Service and the Federal Acquisition Service. GSA has already made significant strides in sustainable buildings, avoiding over $250 million in energy and water costs since 2008. Grasping the potential savings associated with sustainable practices, GSA turned to its Federal Acquisition Service. According to Kevin Kampschroer, Chief Sustainability Officer of GSA, in a statement made to the CDP supply chain program, “GSA is limited in the progress it can make through internal changes, because at least three-quarters of GSA’s estimated carbon footprint comes from vendors, contractors, and supply chains associated with performance of GSA contracts.” Jed Ela, Senior Advisor of Sustainable Supply Chains at GSA, also described the composition of GSA's supply chains as "interesting" as it is "less than half products, more services and leases, waste management, professional services, IT services, and construction.”

As part of a working group with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Defense, GSA issued a report in June 2010 called, “Recommendations for Vendor and Contractor Emissions.” In the report, “GSA concluded that it is feasible, if employing the recommended phased approach, for the Federal Government to track and reduce its scope 3 supply chain emissions through coordination with suppliers and other stakeholders. The reporting of scope 3 supply chain emissions is an emerging field, and all stakeholders will need time and resources to adjust to a steep learning curve.” It is this learning curve that GSA has since worked to reduce through its leadership in the space.

In May 2014, GSA awarded its third generation domestic delivery service contract (DDS3) for UPS and FedEx, making it the first government-wide contract to include specific GHG reporting requirements and evaluation factors. The DDS3 contract requires UPS and FedEx to set company-wide targets for GHG emissions and alternative fuel usage. DDS3 also requires annual GHG emission reports allocated at the agency level based on actual package data including origin zip code, destination zip code, weight, and type of service (ground, 3-day, overnight, etc.). Perhaps most significantly, GSA incorporated a Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) evaluation factor comparing the GHG intensity of proposed services when awarding contracts. The DDS3 fact sheet elaborates,” in awarding the contracts GSA explicitly considered the carbon footprint of the companies' services by modeling the Social Cost of Carbon associated with each company’s expected shipments under the contract.” Put simply, Ela explained, “We get data from bidders ahead of time on what their emissions per package would be and we rolled into the procurement process.”

GSA continued to include GHG emissions provisions in various contracts. The OASIS professional services contract encourages contractors to disclose emissions and though not always mandatory, the contract does state that the reports may be required to evaluation orders placed against the master contract. Among its Managed Print Service providers, GSA also created a new designation of “green” providers for those contractors who have completed a GHG emissions inventory. GSA also designates transportation vendors who are members of the EPA’s SmartWay Transport Partnership, a program that “helps companies advance supply chain sustainability by measuring, benchmarking, and freight transportation efficiency.”

In April 2015, GSA became the first government agency to join the CDP supply chain program. As it piloted the program, GSA made requests of 115 suppliers to publicly disclose GHG emissions and targets. In the 2016 CDP report, Kampschroer stressed, “By disclosing through CDP supply chain, GSA’s private sector partners can prepare themselves to do business with us in the future, as the agency continues to incorporate carbon disclosure goals and performance criteria.” Though only sixty-three GSA suppliers responded in the first year, fourteen suppliers publicly disclosed their emissions for the first time. Of the sixty-three respondents, 85% reported emission reduction investments totaling $11.7 billion with a collective savings of 15.9 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent. The progress made in GSA’s first year of membership reflects Ela’s declaration that “if you want [suppliers] to reduce emissions, the first thing you have to do is ask them to reduce emissions.”

Continuing to pave the way for its fellow agencies, GSA issued the Alliant 2 and Alliant 2 Small Business Contract Government-wide Acquisition Contract (GWAC) request for proposals (RFP) on June 24, 2016. The Alliant 2 GWAC seeks “comprehensive information technology (IT) solutions through customizable hardware, software, and services solutions purchased as a total package.” This potential $50 billion contract RFP notably includes four milestones for contractor disclosure and reduction:

1. Within six months, contractors must publicly disclose sustainability practices.

2. Within twelve months after the initial disclosure, the disclosures must also include a GHG inventory.

3. Within twenty-four months after initial disclosure, the disclosures must include GHG reduction targets.

4. Within thirty-six months after initial disclosure, the disclosures must report on progress towards meeting the GHG reduction targets.

GSA hopes that this multi-step approach will give potential contractors with less advanced sustainability programs or accounting departments the adequate time to develop disclosure and reduction practices to stay competitive in an increasingly regulated space. Ela noted that GSA still requires more market research to determine supplier capabilities, but “where we think it exists, we are trying to get it.”

Ultimately, GSA is leading the way by putting into practice all of the procurement mechanisms that CDP found to be the three biggest drivers of suppliers taking action. Firstly, E.O. 13693 created the public supply chain engagement targets both generally and very concretely with the five contract requirement. Secondly, GSA collaborates internally, with acquisition people working with requirements people to achieve the most successful procurements (see Ela video below). Lastly, GSA has successfully included GHG criteria into contract and RFP language as it leverages its enormous purchasing power to move the needle.

© The George Washington University. All Rights Reserved. Use of copyrighted materials is subject to the terms of the Licensing Agreement.