Capital Partners Solar Project

Harnessing the collective buying power of its partners American University (AU) and the George Washington University Hospital, the George Washington University (GW) finalized one of the largest non-utility solar PV power purchase agreements east of the Mississippi River in June 2014. Under the terms of the Capital Partners Solar Project, Duke Energy Renewables built 52 megawatt of solar capacity in North Carolina that will generate electricity equivalent to approximately half of the university’s on-campus electricity needs, providing significant electricity savings to GW over the life of the 20-year fixed price contract.

By keeping control of the project’s Renewable Energy Credits (RECs), the Capital Partners Solar Project will also help the partnering institutions meet their respective greenhouse gas reduction targets, which for GW is a 40% reduction by 2020 and an 80% decrease by 2040, while AU plans to achieve carbon neutrality by the year 2020. Although it was clear to each organization that renewable energy investments would be crucial components to achieving these climate goals, onsite renewables potential was limited on their urban campuses. As Megan Chapple, Director of the GW Office of Sustainability, said, “Being in the heart of Washington DC…. there’s no way we could build enough solar panels on campus, enough microwind turbines, or make our buildings energy efficient enough to meet our carbon neutrality goals.” A new way thinking was required to move forward.

A New Kind of Partnership

The idea first arose when GW began to pursue the ambitious greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals laid out in its Climate Action Plan. The university began by seeking out advice on different strategies to reduce their emissions. Conversations with thought leaders from supportive organizations, such as the World Resources Institute, Rocky Mountain Institute, and the World Wildlife Fund, encouraged GW to look into renewable energy. GW then decided to form a public-private partnership with AU and the District of Columbia Government and issue a joint request for proposals (RFP) to gauge the market for renewable energy supplies. The RFP attracted competitive bids from both solar and wind energy providers, which, Amit Ronen, Director of GW Solar Institute, explained, was groundbreaking as " a major retail customer of electricity was going out to the market place and asking, ‘who wants to supply us with renewable power.’”

However, the initial request for proposal process highlighted the challenge of meeting differing preferences and timelines of large and diverse organizations, as well as the financial benefits of moving forward separately. So the two private partners, American University and GW, decided to continue to collaborate on a joint deal while the District of Columbia Government continued independently. For GW, who now had a partner in the power purchase agreement (PPA) procurement process, the question then became whether it would be more economical to do something large scale by including additional organizations in the deal. With expert guidance from clean energy consultants CustomerFirst Renewables, GW and AU formed the current Capital Partnership by adding in the George Washington University Hospital (which is located on GW’s Foggy Bottom campus but is an independently owned and administered institution). It was thought that by bundling the demand of several large institutions, the RFP became more attractive to third party energy providers, increasing the numbers of bidders and improving pricing offers.

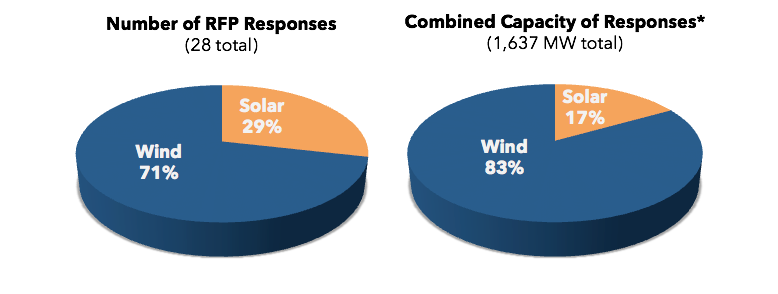

As the chart above indicates, the RFP received 28 responses, with the majority coming from wind based projects. It was noteworthy that the total number of bids seems to indicate that there are at least 1.6 gigawatts of economically feasible projects in the Mid-Atlantic region despite its reputation for having relatively poor renewable energy resources.

After reviewing all the bids and weighing factors important to their organizations such as pricing and company reputation, the Partners chose Duke Energy Renewables (a subsidiary of Duke Energy, the largest private utility in the country) to supply the contracted renewable power and be responsible for building, operating, and maintaining the three large solar farms in northeastern North Carolina.

PPA Financing Made Sense

While the manner of collaboration was groundbreaking, the basic principles of the power purchase agreement (PPA) financing model still applied to the deal. For example, Duke Energy Renewables acts as the third party responsible for all economic and technical aspects of the solar projects, without any funding or resource required from the contracting party.

From the Capital Partners' perspectives, their electricity bills would look essentially like their historic bills, once the negotiated PPA rate that covers about half their electricity needs is blended with pricing for electricity contracts that supply the power needed meet the other half of their demand.

The PPA also provided a vehicle for non-profit organizations like GW and AU to take advantage of state and federal incentives. In this case, the ability of Duke Energy Renewables to monetize the 30% Federal Investment Tax credit and North Carolina’s 35% renewable energy investment corporate tax credit greatly boosted the project’s economic feasibility. While the exact pricing structure remains proprietary, the amount that the Capital Partners are paying for electricity is less than the cost of electricity on the open market, and the price is fixed over 20 years. This will likely save the institutions millions of dollars in avoided electricity costs and protect them from future price volatility. So, while sustainability goals encouraged the project’s inception, the long term financial benefit of the PPA ultimately made it possible.

Buying Within the PJM Interconnection Grid (PJM)

A key criteria during the RFP process was to require that any renewable electricity generated occur inside the borders of the PJM regional transmission organization which manages the grid for the Mid-Atlantic region. That was important to the Partners because otherwise they would not be able to claim that the clean electricity generated by the North Carolina project was displacing more carbon intensive supplies elsewhere in the region.

As a point of clarification, as with any off-site source of electricity generation, it cannot be said that any of the resulting electrons generated in North Carolina are directly powering any lights, computers, or equipment on the Partners’ DC based campuses. Technically speaking, any electron generated by any electricity source will always serve the demand closest to it on an interconnected grid. In other words, only a renewable energy source co-located with its demand source, like rooftop solar, can accurately say it is powering onsite demand. But by using a PPA to guarantee a single long-term purchaser of both the resulting electricity and associated RECs, the Partners can legitimately claim that but for their actions this new source of clean power would not have come online and decreased the use of other carbon intensive sources elsewhere on the grid.

Lessons Learned During a Long Process

The partnership and the PPA provided the institutions with many benefits, but there were still many challenges throughout the procurement process from which to learn from. A goal of the Capital Partners Solar Project was to “provide information on lessons learned so that other institutions and potential suppliers can pursue similar arrangements more rapidly." Chapple and other proponents of the solar PPA believe the three year long process can be streamlined in order to benefit and apply to a varying range of new customers seeking an economical solution for clean energy procurement.

One of the first roadblocks was getting multiple layers of institution leadership agree to purchase electricity in a whole new way. For some, this involved considerable education and understanding of the PPA process and the potential risks of locking in a fixed price for electricity over 20 years. For example, despite the predictions of most analysts and historic norms, there was concern that electricity prices might decline over time and the University would be locked into a higher priced contract. In fact, this was one of the reasons the Partners decided to limit the amount of PPA contracted electricity to half of their anticipated future demand. The flip side of this argument is that locking in a fixed price protects institutions from both future electricity price increases and market price volatility for which it can be difficult to plan and budget.

Another key lesson from the PPA procurement involved the negotiating process. One of the biggest obstacles was reaching consensus on more specific contract details between three independent and large organizations. Electricity markets can be complicated, relevant pricing and other data can be difficult to obtain, and the Partners did not have in house expertise on these issues. To facilitate understanding of these issues, the Partners engaged an outside vendor with considerable market knowledge and experience with electricity contracts. The vendor also served as a go-between the bureaucracies of each partnering organization, but the costs and benefits of bringing in an outside broker or vendor should be weighed accordingly.

Climate Action and The Future

Eighty percent of GW’s greenhouse gas emissions come from energy usage in buildings across three campuses. Before the Capital Partners Solar Project PPA, GW’s greenhouse gas emissions peaked at over 100,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. After the project, the University will be able to claim emission reductions of approximately 60,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, the equivalent to taking 12,500 cars off the road or the carbon sequestered by 50,000 acres of U.S. forests.

As described above, the PPA not only benefitted both Duke Energy Renewables and the Capital Partners financially, but it also met the shared Partner goal of meeting their environmental commitments using a more proactive approach than just buying offsets or RECs on the open market with no tie to a specific project or regional outcome. The third-party financing structure enabled the urban entities to benefit from a low carbon future that requires space otherwise unavailable to them in the district. American University President Neil Kerwin said that with the help of the PPA, “American University is on its way to achieving carbon neutrality by 2020.” GW’s Chapple also said, “imagine the impact if other universities, colleges or municipalities did the same.”

© The George Washington University. All Rights Reserved. Use of copyrighted materials is subject to the terms of the Licensing Agreement.